Where the Rubber (Factory) Meets the Soccer Stadium

What's old is new again as Denver debates community benefits in exchange for city $ to build a professional women's soccer stadium on a site with rich worker and community benefits history.

One of my favorite yet befuddling quirks is when locals reference landmarks known mostly [nay, only] to them when giving directions to a foreigner. Like “turn left where the coca-cola plant used to be” or “it’s right after the old highway.”

In spite of the fact an estimated 1/3 of Denverites never saw it IRL, because they moved here or were born after its demolition in 2013, I’m guilty of confusing people in just this way by navigating to or from the “Old Gates Rubber Factory.” As if everyone should know that a sprawling brick campus with an iconic water tower stood at I-25 and Broadway for around 100 years. It will always be the Gates site to me, because it’s where my career in community organizing and public policy, and a movement for equity in redevelopment, began in Denver. (See below).

Now, it’s usually just “I-25 and Broadway.” Real estate interests call it Santa Fe Yards, but I question whether anyone in the community really calls it that? Local news followers now know it as the proposed site for the second dedicated professional women’s soccer stadium in the world.

Denver’s Mayor has received the first of numerous approvals required from the Denver City Council to move toward allocating $70 million to buy and improve the site for Denver’s newly selected National Women’s Soccer Leage (NWSL) team.

In an exercise of checks and balances between branches of government that Congress could take a lesson from, City Council scoured the proposed deal, brought transparency to critical details, and won financial and other concessions that better protect the city and could result in more equitable outcomes through a community benefits agreement.

To skip the history and jump to my takeaways on the stadium deal, click here.

Can We Live up to the Gates Factory Legacy?

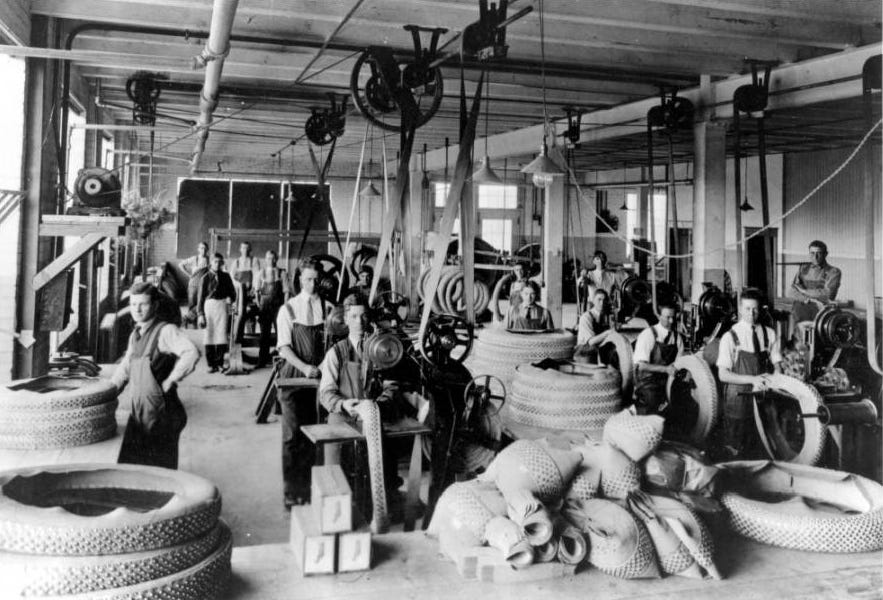

Workers at the Denver Gates plant were unionized, represented by the Denver Local #8031 of the United Steelworkers of America. They retired with pensions for their hard work. The company was lauded for fostering strong employee community, wellness, on-site groceries at discounted rates and an on-site health clinic.

When I worked with the community surrounding Gates, we spoke with Gates retirees and their descendants. They shared an oral history that the plant was “one of the first to be racially integrated” during a time when many others remained segregated.

OPPORTUNITY: When asked whether stadium construction will be done by union workers during council committee, controlling team owner Rob Cohen said he didn’t know. He referenced prevailing wages, which do help level the playing field. But unions also provide workplace protections, guaranteed health care, pensions and other unique benefits. Apprenticeship training, where workers earn while they learn, can be provided by union or some non-union companies. Unions have a longer history of doing so and graduate more apprentices for careers in construction.

NWSL Soccer players are also unionized, represented by the NWSLPA. Though everyone acknowledges their collective bargaining agreement has a way to go in lifting the minimum salaries for players, which is at $48,500.

OPPORTUNITY: This ownership group will have a voice in future owner/union bargaining. They can and should represent Denver’s values, which has voted overwhelmingly in support of collective bargaining, to raise women players’ salaries.

OPPORTUNITY: When a CBA is negotiated, unions representing future jobs on the site should be included, to honor the Gates’ legacy and advocate for future workers. For example, UNITE HERE represents concessions workers at Coors Field.

Denver’s Legacy of Public Subsidies Serving a Greater Good Began at the Gates Site

Two decades ago, Denver’s first foray into “community benefits” in big, subsidized redevelopment projects began at the very same site now proposed for the stadium.

Shuttered in 1991, the Gates Corp began what would become a decades-long odyssey to sell the site for redevelopment. A development partnership under the name Cherokee Partners bought the half west of Broadway in 2001. They asked the city for $41 million in metropolitan district taxing authority (to tax themselves) and $85 million in tax-increment financing (TIF). TIF captures new city sales and property taxes generated by new development and gives it back to the developers to reimburse them for agreed upon infrastructure costs.

Thus began Denver’s first ever “Campaign for Responsible Development” to ensure city subsidies delivered community benefits, not just corporate profits. I worked for the organization leading the charge. Our goal was to win Denver’s first-ever signed agreement with a developer on socio-economic benefits: a CBA.

In 2001, Baker neighbors, labor unions, Section 8 housing residents, disability advocates, and conservation organizations organized to get Cherokee to the table. We met heavy resistance. A favorite quote from city officials: “the development is the benefit.” We had a “vocal minority able to get attention” who supported us from the city council, led by Doug Linkhart and Rick Garcia . But not a solid majority.

We both won and failed.

The only signed agreement was to exclude a big box grocery store, which protected nearby unionized grocery stores from being undercut by non-union, big-box competitors paying lower wages without health care. We also won expansion of city wage policies, environmental transparency and other commitments. The biggest win was significant affordable rental housing. These commitments were memorialized only in agreements between the developer and the city, not with the community.

It wasn’t a CBA, but they were ground-breaking benefits, so we supported the city subsidies. And we changed the conversation about subsidized development forever.

Broadway Junction, a 60-apartment affordable building serving very low-income tenants was the first thing built on the site.

But the Great Recession hit and Cherokee sold the rest back to Gates. Broadway Station Partners bought the site and renegotiated the TIF subsidies in 2017. They also renegotiated the original affordable housing agreement with the city, seeking to reduce the affordability commitment by raising the income levels that housing would serve. Only because I served on City Council was I able to jump in and wring out a commitment to reserve some apartments for residents with Housing Choice (Section 8) Vouchers, to preserve some of the originally negotiated intent. The community had no other seat at the table when this happened, because there was no CBA.

Under that revised commitment, a second affordable housing project is now in the works by Archway Communities, for 150-180 affordable apartments. Additional affordable homes should also be mixed into any market rate housing on the remainder of the site. However, city staff informed council at committee that a few of the stalled projects have eliminated residential or reduced plans to build below maximum density.

The stadium is now planned on the north end of the site that remains unsold.

Through all these fits and starts, remediation and some site infrastructure continued, as did some reimbursement of those costs with TIF dollars.

Your Cheat Sheet on the Stadium Deal

Economic Benefit

Upon Council request, the city economist produced a study estimating huge outcomes if the stadium is built. An eye-popping $2.2 billion over 30 years in direct (construction and spending in the stadium), indirect (spending at nearby businesses) and induced spending (the things the employees of the first two buy with their earnings). The Denver Post cited peer-reviewed research dialing down the true outcome of sports venue subsidies. Councilwoman Sarah Parady taught a graduate course on the “substitution effect” during the final council floor debate on the Intergovernmental Agreement (IGA) framing out the deal: you have to subtract out spending that would have happened elsewhere anyway, and therefore can’t count all spending as “new spending” due to the stadium.

The counter-arguments: 2/3 of pre-reservations for season tickets have come from outside of Denver, indicating new revenue to Denver (maybe at the suburbs’ expense). The success Kansas City attributes to its own NWSL stadium. And the benefit to struggling South Broadway businesses.

No new sales or property tax dollars on the Gates site will flow to the City for 17 years, because they’re already being reinvested into the site through the TIF. But the city would capture any net new taxes generated off-site due to the stadium.

The developer has flipped flopped in committee meetings, media quotes, and in Council briefings (according to the floor debate) about whether they intend to seek TIF reimbursement for their own stadium costs.

Whether there would even be enough left, and if so, whether they get a slice, will be a BIG topic of negotiation before the final Council votes to rezone the site and actually allocate the city’s dollars, expected late this year.

Key takeaways on the economics: Mixed

Some degree of increased economic activity in the city from the stadium’s construction seems real. Certainly less than estimated. But hard to measure prospectively or even retrospectively, because of the number of constantly changing factors beyond just a new stadium. Not a rationale for supporting a $70 public investment in a stadium by itself.

Increased business to a nearby, historic South Broadway district that has struggled for two decades with a gaping vacant donut hole next door is a better, narrower case for this investment.

The Council made this a better deal by removing a clause in the first draft of the IGA that would have directed any excess TIF dollars to the stadium owners for its construction before it reimbursed the City for the improvements we fund. This is what checks and balances look like.

IF there’s enough TIF left over, and IF the final deal does allocate any subsidy to the stadium’s construction, then the total subsidy will be > $70 million and the city needs to be transparent about that. The larger the total package, the more important it will be for the other benefits to balance the subsidy out.

Amenities

Land. They’re not making more of it. A key difference between this deal and many local and national sports stadium subsidy deals is that taxpayers aren’t forking cash over to a team. The city will be buying the land and will get it back without paying more if anything goes south. Never built? City gets the land back. Belly up? City gets the land back. According to a sports consultant who spoke at Council, the Bronco’s stadium has a similar clause. But let’s hope we aren’t facing that scenario soon, right?!

The I-25 site is highly constrained by freeways and highways. The site already has one pedestrian bridge and plans call for a second. Under the original site plan from years ago, and now the revised and final soccer stadium IGA, both are to be funded by the quasi-governmental metropolitan district through which all these deals run.

The stadium IGA has the city funding a new Vanderbilt Park East that will be adjacent to the stadium, and improvements to Vanderbilt Park West across Santa Fe.

Amenity Takeaways: Mostly Positive

The city’s right to retain ownership of the land is one of the biggest clinchers making this a better deal than average.

Council made this a better deal by catching and removing a clause in the first IGA draft that would have put the city on the hook for building that second bridge (for an unknown price).

As emphasized by the District Councilwoman, Flor Alvidrez, the sidewalks, transportation connections and park improvements were all needed in this community regardless of the stadium.

Community Benefits

Sports arena developments in Denver and across the country have become ground zero for CBAs to balance out the cost of public investments and improve the politics of passing public land or subsidies. Sometimes, it goes well. The community wins significant housing affordability (in surrounding development), local business opportunities, community funding and/or other amenities, such as:

Ball Arena here in Denver, the largest agreement on an approved project in Denver’s history (Park Hill Golf Course CBA was even larger, but the project went down at the ballot box)

Nashville’s MLS Soccer stadium

Staples Center in LA

Sometimes it doesn’t go as well:

Philadelphia went around the community to negotiate its own community benefits on a downtown Sixers arena that the community didn’t sign off on, only to have the team pull out of the entire project just days later

A vague and unenforceable agreement with the Buffalo Bills

CBA Takeaway: TBD

No one project can afford to solve every community challenge or ask. The owners will point out, with evidence behind them, that NWSL teams aren’t yet profitable. But finding a path to a CBA has already been established by a clear majority of the Council as necessary to secure the money for the land. And the team has already agreed to enter into negotiations.

The balance of this deal will turn on some of the following:

The authenticity of the community parties on the other side of the table. It must be an independent, diverse and representative coalition of neighborhood, non-profit and relevant interests with a stake in the socio-economic equity outcomes of the project. The developer’s materials often mention community listening and engagement. These are NOT the same as a CBA.

A coalition must have the resources to equalize some of the power owners hold, in an intense, time consuming, sometimes technical and always legal process.

The value and impact of the actual benefits. These should come from the community via the coalition, but could include:

Councilmembers have raised the potential for a “seat tax” (paid by ticket buyers, not the team) to fund youth programming, team funding for youth sports etc.

There’s been no mention of the stadium owners themselves actually developing the mixed-use around the stadium. And there is already a housing affordability agreement on the site. So, unless I’m wrong (and I reserve the right to be), or something changes, housing affordability is a tougher fit for this CBA.

Mitigating displacement risk in the surrounding community.

So many other topics could come up: free/reduced tickets, arts and culture, small or employee-owned business opportunities, conservation practices etc.

Gender Equity

Owners have organized supporters from around the world to lobby council, that a “women’s team is the benefit.” And that its only fair for Denver to subsidize women after we’ve subsidized men. Many have cited intrinsic and unquantifiable benefits of building community and culture through sport in a city.

As a good lesbian, and a soccer mom, I’m on the women’s professional soccer bandwagon, believe me. But there’s a fair argument to be made that a big reason why women have been so screwed in all professional sports is because of the fucked-up structure of the entire corporate sports enterprise itself. And the equally fucked-up game of blackmail teams play with cities for taxpayer funds. Oh, that we didn’t have to choose between supporting NWSL in Denver and feeding the beast, at all, right?!

As you tally the takeaways and hassle our Councilmembers to vote the side you came down on, please just remember:

We need all kinds of leaders. Those who decide based on the rules as they exist in the world today. Those who ask hard questions and create space for community benefits to improve these deals, regardless of which side they land on. And those who make hard votes that hold the line for the better world we wish for tomorrow. Women’s interests can be advanced by each.

Can you spell b.o.o.o.d.o.g.g.l.e.? I know you can!

Robin,

Unless I missed it, you omit two relevant facts:

1. There is a perfectly good professional soccer stadium in Commerce City. The Avalanche, Nuggets and Mammoth share a venue for over 80 days a year. It seems that two professional soccer teams could do so for approximately 20 dates each. Is this just a vanity project for Denver?

2. Your analysis of costs and benefits does not examine the comparative benefits of alternative uses of the $70 million in spending. But, of course, that is the only rational way to evaluate this expenditure. I would very much like to see the city develop alternative scenarios for spending these funds, e.g. at the new Park Hill Park, and then compare costs and benefits.

If you covered these in your presentation and I missed them, I apologize.