The future is going to be local. Unfortunately, not female. Yet.

But thanks for all of the appreciation you shared with this female leader for my ballot measure guide—it makes this whole side gig quite rewarding to know you find it helpful and shared with so many others.

The national election will reverberate through all of our lives, even in the blue bubble of Colorado. Likely more so for our immigrant, transgender and other politically targeted neighbors. But we’ve been through this drill before.

The local decisions we make are powerful immunizations. They don’t cure national ills, but can reduce hospitalizations and deaths none the less.

Local communities have largely been on our own with the affordable housing crisis for a long time. The best navigation begins with knowing where you are on the map. So I offer a couple local and national pin points and turn by turn directions on this topic at the top of voter’s minds, if not their votes.

Making Sense of Mixed Housing Messages

Why Denver and Adams Sales Taxes Went Down

Today’s likely going to be a hard day for Denver Mayor Michael Johnston. At 5 pm the next round of ballot counting is likely to confirm what the last few days previewed: that 2R, his proposed sales tax for affordable housing, is going to fail in a close vote (unless the trend of the remaining votes to be counted completely reverses course by a 2 to 1 margin, which almost never happens). No one should take a loss to mean housing isn’t a top issue for Denverites/voters (not exactly the same thing, of course). Or even that we aren’t willing to pay for it. As we’ll explore.

Adams County’s similar sales tax proposal for housing, 1A, was also whomped down by 70% of voters. I’m not a close enough observer of Adams County politics to comment deeply. But I’m aware that, unlike Denver, voters there are skeptical of most tax measures, frequently voting down funding for schools and other measures (including this cycle). So they had a higher hill to climb regardless of the details. And one important detail appears to be the lack of any registered committee spending any dollars on a paid campaign to climb their hill (according to the state TRACER campaign finance system).

5 Take Aways/Questions For Affordable Denver’s Failure

Wrong tax for housing? Denver and Adams were outliers nationally in proposing sales tax for housing. Property tax backed bonds are far more common. In the few places sales tax is used elsewhere, measures often focus on homelessness. Just as we did with the Homelessness Resolution Fund that voters approved handily in 2020. While I believe Johnston’s rationale that polling favored sales over property tax, I also suspect the drum beat of rhetoric surrounding billionaire ballot measures and resulting political wrangling at the capitol heightened voter sensitivity to property taxes during this period. Only 7% of Denver voters in June 2024 cited property taxes as an important concern in response to an open-ended question. And voters are handily passing a property tax-backed bond for DPS schools as we speak (albeit without a tax increase).

Experienced observers will note that while sales taxes often pass in Denver, they’ve performed worse and sometimes fail in precincts with the highest number of renters and working class residents—voters also struggling the most with housing costs. A mismatch between the potentially best target housing voter audience and the source.

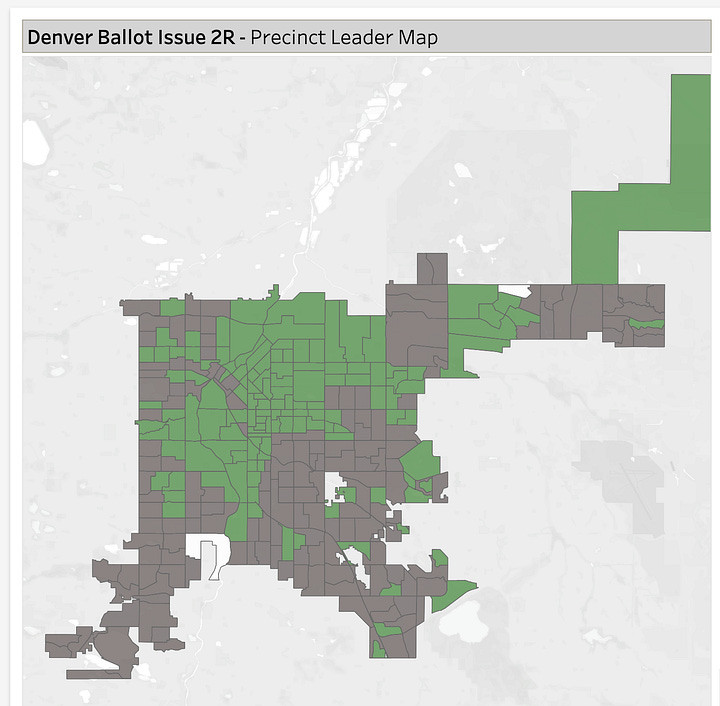

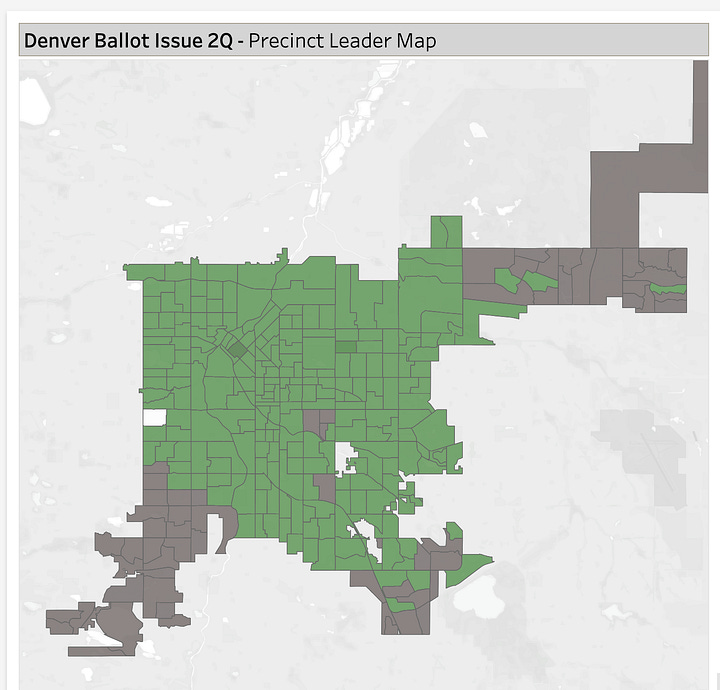

But be clear, 2R’s failure can’t be blamed on voter resistance to sales tax alone. Denver Health’s tax is passing by a healthy 56% margin. Yes, it was slightly smaller than the housing tax. But my gut says that doesn’t explain the differences in these maps:

Denver Support for Housing (Left) and Denver Health (Right) Taxes

Denver Clerk and Recorder as of Thursday at 5 pm (63k votes left to count out of 359k)

Did those struggling the most fail to see themselves in the Mayor’s frame? The Mayor went out of his way to describe this as a “middle class plan.” He talked a lot about homeownership and referenced teachers and firefighters the most (though he also mentioned restaurant servers). These have been the go-to faces of affordable housing campaigns in more conservative communities. Conventional wisdom and some polling says that people who don’t need affordable housing themselves are more favorable to funding it when campaigns focus on “likable” recipients and avoid invoking stereotypes, namely that the funding is going to help other/poor/black/insert any other population perceived to be less popular with white homeowner voters here. Clearly Denver’s pitch designed for conservative voters failed. While the more conservative and highest voting section of the city, SE Denver, voted for the Denver Health sales tax, they’re shooting down 2R. (The most conservative, SW Denver, often votes against new sales taxes and predictably hates both).

And in messaging for a conservative audience they were less likely to win, a campaign that surely hoped to rely on progressive, working class, and BIPOC voters didn’t put the focus on them. So far, the campaign is losing in some of the West Denver and NE Denver neighborhoods where working class voters with the most at stake live.

No plan. I’ll be the first to admit that the average voter isn’t as wound up as the wonk that I am about the failures of this proposal to build clear consensus and use a data-driven approach to lay out a clear plan of where it would have a focused impact. But I heard from many voters across the income and renter/home owner spectrum who were uneasy and said things like “I don’t understand what it’s really going to do.” There’s wisdom in the collective electorate, and I believe these voters were telling me the difference between the laundry list the Mayor repeated ad nauseam and a concrete plan they could count on. Housing campaigns in cities not dissimilar from Denver have given voters these kind of details and passed their measures (Charlotte, NC this cycle and Seattle previously).

Overpromising? I’ve been privy to local, state and national polling on housing over the years. There’s an anomaly that can often only be discerned by looking across many different polls and kinds of questions: voters often support specific initiatives or proposals to “do something” about affordable housing, even while a majority remains skeptical about whether the challenge can be “solved.” Again, the collective wisdom of voters know that complicated market factors are involved in housing. And they—rightly—have questions about the government’s ability to “fix” it completely. 2R’s sole spokesperson repeatedly used language about the measure meeting “all” of Denver’s gap in housing. Mentioned “no one” paying more than 1/3 of their income for rent. The visionary and hopeful traits for which we love and elected the Mayor run smack dab into voter’s trust when he promises things that he can’t, and they know he can’t, deliver. Even with $100 million/year. The impact of these overinflated promises was likely greater in the absence of a concrete plan outlining specific *impacts* the money could have made.

Contrast this approach with Denver Health, which promised only the modest outcomes it could deliver. Keeping the hospital solvent and the doors open. Opening a few more beds for mental health and substance misuse. Shoring up school health clinics. Donna Lynn and team didn’t promise to eliminate all health disparities or solve the mental health crisis, though I bet they aspire to those outcomes as much as Michael Johnston wants to solve housing. But they weren’t out to prove something. They told Denver the money would make a difference and voters rewarded them with it.

Better as a team sport? Yes, the Mayor had council co-sponsors. Yes, the campaign included lots of endorsers and some grassroots volunteers. But no one who watched the process unfold could be confused: this idea came from one man and was driven by that man from start to finish, with some hard fought exceptions during the Council process. He determined what spending ideas were in the public domain (down payment assistance and wonky rental finance models most voters don’t relate to), and which were not (emphasis on building affordable rental housing for those the market is failing, and housing for those exiting homelessness). Endorsers did not enjoy a sense of shared ownership over the framing of how these funds would be used. Just the hope that slices of the pie would fall well when they were divided up later. Though it may be harder to measure, I posit that a lack of consensus and communal ownership over a strategy matters to the success of a campaign.

So what next?

Do the work we would have on analyzing needs and gaps anyway. Denver has to do a Housing Needs Assessment by 2026 anyway under SB24-174. Don’t wait. And don’t do it on the back of an envelope. Hire. Independent. Experts. Who have already analyzed gaps and opportunities for Denver and other cities.

Price out scenarios for filling the gaps. Yes, a little something for everyone. But most where we can leverage the most outside money and the needs are greatest. Focus on building lasting affordable housing. Before allocating funds to one-time assistance that the team thought sounded good for the campaign, but neither resonated nor create actual long-term affordability. Build. Consensus. Among. Stakeholders. At the same table.

Look at funding sources again. For those stuck on the regressivity of sales tax, property tax does have more proportionality built in. Those who can afford more expensive homes pay more. A property tax backed bond for housing and shelter has passed in Denver before. They’re proven nationally. Time limited. Or, Denver’s existing property tax mill for affordability gets ratcheted down every 2 years. We could shore that up for a more evergreen source of funding. Or look again at sales tax when we have overcome the other shortcomings above.

The Mixed Messenger in Chief of the United States

Wishful thinkers are seizing on off-the-cuff remarks Trump has made complaining about zoning and promising to reduce government regulation to speed the building of housing. They’re framing it as a “change of heart” from his earlier and frequently repeated promises (including this cycle) and actions (in his first administration) to “defend single family zoning, local control and the suburban way of life from the threat of low income housing.”

Don’t bet on the kind of zoning changes housers are thinking about. And not just because there’s really limited federal power in this arena. Even if he pursues incentives or links to federal funding, the kind of regulation he wants to jettison is environmental, because he wants to build on federal lands. Maybe zoning that limits sprawling single-family homes and the climate impacts of that sprawl. And surely fees and taxes. He’s a master of telling audiences what they want to hear. But he hasn’t said a word about density, gentle or otherwise. And apartments or condos, outside those with his name? The man is a populist who knows something YIMBYs and re-branded abundant housing advocates don’t seem to yet:

The framing of growth through rampant upzoning as the answer to affordability is *not* winning over the general public. It reads like an attack on single family homes. Which every American has been programmed for generations to dream for because we’ve seen it and been told it is the key to building wealth.

If this election has taught us one thing that Donald Trump knows, it’s that facts and data don’t win the hearts and minds of the masses.

I’ve spent the last year outlining a path for both wider political support of land use reforms and better housing outcomes. Going forward we need to:

Talk differently about land use reforms and growth, stop talking down to people as if they are “wrong” for where they live or what they dream about

Tie the land use ideas that data tells us can help to values (aka single family homes AND townhomes can help more people build wealth)

Be honest about what the market can and won’t do (don’t talk to me about zoning reform if you’re not also supporting funding for below 60% of AMI rental that we know the market isn’t going to deliver in high cost markets anytime soon)

Pair land use and equity strategies in both our framing AND our policy-making

We can and should use a progressive page out of the populist book to approach zoning as a key strategy for housing. And it’s a good thing Denver City Council is primed to have that conversation to keep things moving forward as the expanded funding train appears to be paused.

My Role in What Comes Next

I can’t imagine a better place to process the election results and build the pipeline of local leaders we urgently need than my new day-job home: University of Colorado Denver’s Political Science Department. I’m leading the Center for New Directions in Politics and Policy, a graduate program focused on those seeking to make an impact in their local community. (Let me know if you might be one of those people!)

I’m going to keep on consulting on local policy on the side. And as long as you keep reading, also keep writing and commenting. While all opinions will be my own, and some will be strong, I’ll remain committed to contributing thoughtful and respectful dialogue to the public domain.

On that point, I’m done with Twitter/X and you should leave too. Not because of the election results. But because of how the platform skews reality and fuels hate. The Substack feed is an intelligent and civil alternative if you’re looking for one. Threads hasn’t done it for me, but good on you if it does for you.

And I’m always happy for your thoughtful contributions in return.

Hi Doug, you know I'm a champion for more affordable apartments. But with an inclusionary housing ordinance like Denver and 6 other metro communities and many mountain communities have, we DO get affordable homes within every project of market rate/high end housing that is built (8% to 15% depending on the city or policy). They aren't separate things and no government can make a developer build 100% affordable housing. My research also shows that we need housing at all incomes, some of the worst housing cost increases have happened in neighborhoods with very little new development. It is a both/and, not an either or. We have to allow building of market rate housing, capture some of it for affordable, and building dedicated affordable which does require public subsidy. I agree this tax could have been framed much more clearly for voters to understand what it really did, so hear your concern about just "subsidizing builders" without knowing which kind of housing they were building.

There has to be more control on building permits and sales. Stop approving high end apartments and condos so developers are forced to build more affordable ones. And limit or outlaw sales for short term rentals. This tax felt like we would be subsidizing builders.